Biafra War Memories: Fifty Years On

Oguta Lake

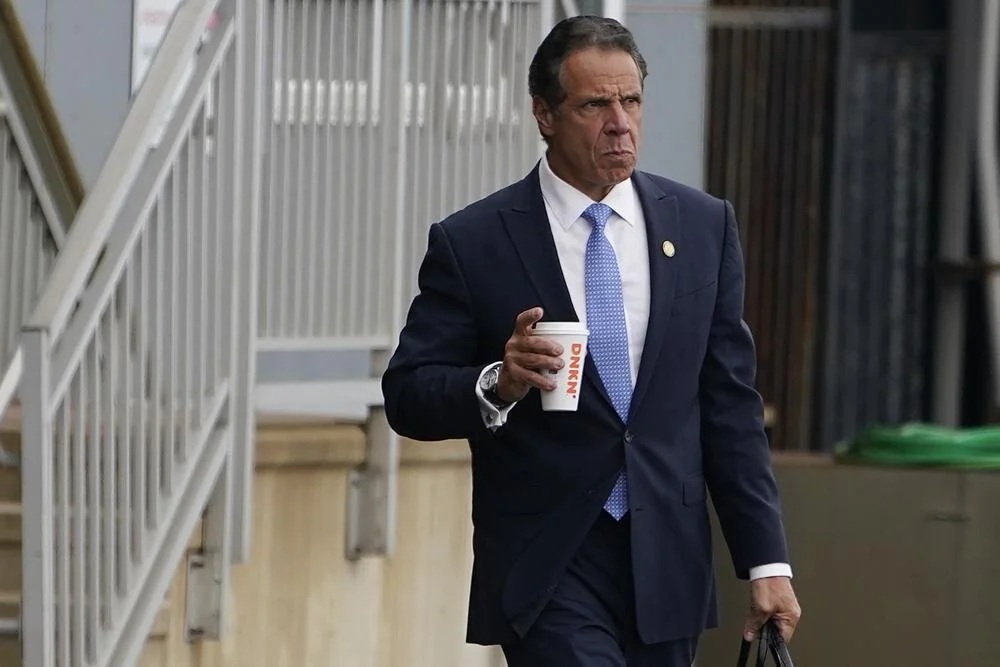

Photo: Shayera Dark

January 15, 2020 marks fifty years since the guns of war officially fell silent in what was Biafra, a republic born out of a secession and carved out from Nigeria’s south-eastern region—home to the Igbo—the country’s third-largest ethnic group—and various minority tribes, some of whom weren’t supportive of the split. From 1967 to 1970, Nigeria and Biafra were locked in a brutal civil war that claimed more than one million lives and displaced countless others.

The reason for secession was due, in part, to the federal government’s weak response to the massacre of south-eastern civilians, mostly Igbos, in northern Nigeria following the counter coup in 1966.

As Nigerian soldiers advanced and towns and cities across Biafra fell in their wake, refugees escaped to safer areas, seeking refuge in the homes of friends or strangers. Others lodged in schools and were catered for by charities. Oguta, a small lakeside town in south-east Nigeria, harboured refugees until September 1968 when a military invasion from its waterways forced civilians to flee.

The town’s proximity to Uli airport, an airstrip 16 kilometres away that served as Biafra’s major supply line for arms and relief material, made recapturing it an existential necessity.

“If Nigeria got a foothold in Oguta, the airport at Uli, which was our major link to the outside world, would have been in jeopardy,” said Colonel Emmanuel Nwobosi, chief of staff to Biafran Leader General Chukwuemeka Ojukwu. “They would have also sent reinforcement by the seaway into Biafra.”

As such, Ojukwu personally oversaw the battle for Oguta. Five days later, it was liberated.

Though the battle was brief, for Oguta civilians, the impact was no less life-changing. To date, memories invoke a combination of pain and grief for the loss of innocence, possessions and loved ones in the war for self-determination.

Bennett Okororie, School Principal and Scout Recruiter

Just before the war started, I was in studying English Classics at the University of Nigeria (UNN) in Nsukka. I’d gone to UNN after four years as principal of Kings College of Commerce in Buguma, Rivers State, where my family lived. Our graduation ceremony had been scheduled to hold the day after the war was declared. We had an emergency ceremony at 10pm but weren’t given certificates. It was rushed. Afterwards, I returned with my family to Oguta in a hurry as Buguma youths were hostile to Igbos and the Nigerian army was advancing.

Life in Oguta was normal, but gradually we felt the impact of the war. Since schools were closed, I summoned children and taught English every morning. My house was full. Their parents wanted to pay for the lessons, but I refused.

I was appointed Chief Intelligence Officer by the Biafran air force. My duty was to recruit intelligent young men and women to work as scouts. They were to identify spies who snuck into Oguta, which was a strategic location due its proximity to Uli airport. We made a number of arrests. Once, a young man resembling General Ojukwu came into town. A female scout spotted him and we strategized on how to trap him. He was caught with a map of Oguta and taken to Ojukwu.

The Nigerian navy invaded Oguta through Orashi River which feeds the lake. People fled town when their gunboat came ashore. I sent my heavily pregnant wife ahead of me to the neighbouring town of Mgbidi. The next day we managed to reach Omuma, our refuge destination.

A week after Ojukwu announced Nigerian soldiers had been swept away, I returned to Oguta to fetch my wife’s sewing machine and yards of fabric. There were dead bodies lying around town like broken stones, something I’d never seen in my life.

When I arrived home, the brand new machine hadn’t been looted. I packed the fabric and other items on my bicycle. As I attempted to head back to Omuma, Biafran soldiers arrested me for disobeying Ojukwu’s directive, demanding Oguta people return. They took me to their commanding officer, who eventually let me go. On my way out of his office, I spotted my transistor radio among many others that Biafran soldiers had been looted from homes. After a short argument, I showed him my ID, which matched the name on the radio, and he gave it back to me.

Doris Nwobi was a primary school pupil when the Nigeria-Biafra War broke out.

Photo: Shayera Dark

Doris Nwobi, Primary School Pupil

I was in Primary 5 when the war broke out. My parents and I were living in Port-Harcourt at the time, but we were forced to flee to Oguta when the city fell. I didn’t continue my primary education in Oguta until the war ended.

The Catholic Church in Oguta operated a soup kitchen for Biafran refugees, and apart from the fact that children weren’t going to school, everything else seemed normal to me.

My family didn’t really suffer during the war. My uncle was part of Biafran Organisation of Freedom Fighters, a paramilitary group, and had access to relief materials which he supplied to us. My father started a betting shop, while my stepmother made trips to the Midwest to trade. It was a dangerous journey since the market was behind enemy lines. But women who came back to Oguta with scarce commodities made a lot of money.

The day Oguta fell, my family was the last to leave our village because we were waiting for my uncle who had gone to get fuel for the car. There was a lot of gunshot and shelling. We were scared, especially my father. It’s not something one should experience twice.

Fleeing neighbours kept asking, “Ndibe Nwobi, why aren’t you moving?” Finally, my uncle returned and we drove in my father’s car to Amiri, a nearby town, where my grandfather’s friend offered us refuge.

The battle in Oguta didn’t last more than a week. My family returned a week after the Nigerians were defeated. My village, Abatu, was intact because it was at the end of town. But from Umude village to Umuenu, the houses were looted and torched by retreating Nigerian soldiers.

When the war ended, we had surplus yams ended as a family friend had brought 100 tubers prior to the invasion for safekeeping. But he never came back for them. My guess is the man died.

Evelyn Okororie lived in Port-Harcourt before the war. She fled to Oguta when the city fell.

Photo: Shayera Dark

Evelyn Okororie (not related to Bennett), Businesswoman

I made a living selling clothes in Port-Harcourt until the city was captured by the Nigerian army. Pandemonium broke out as people tried to escape death. We were being shelled from everywhere. Rivers men killed Oguta and Igbo people they stumbled across. Men abandoned their pregnant wives as they gave birth in the open.

There were no vehicles available to transport me and my seven children to Oguta. We trekked all day to the city of Owerri, with only achara (a vegetable similar to leek) to assuage our hunger. On the way, an Oguta man with a car offered to relieve me of my belongings. It wasn’t until we got to Owerri that we found a vehicle to take us to Oguta. I returned virtually empty-handed from Port-Harcourt as I had to sell my property.

In Oguta, I went to Afia attack, a market in Nigeria’s Midwest region. The treacherous journey took two days on foot. Some women on the trail were raped and killed by soldiers, others died in bombing raids. We sold food, clothes, and plates to Nigerians, and in return they give us Nigerian currency to buy items that included cigarettes, weed, potash and salt for sale in Biafra.

In November, two months before the war ended, a Nigerian warplane attempted to bomb the military encampment next door to my brother’s house, but the missile missed its target. I lost my mother and 3 children—two boys and a girl. My brother’s daughter also died. About 20 people perished in the bombing that day. Upon my return from the market, I cried. What else could I do? I looked for death but couldn’t find it. The crosses I bared that period were large, so nothing scares me anymore.

I opened a restaurant after the war. Nigerian soldiers stationed in Oguta patronised me. I served them on credit and they always paid me at the end of the month. I bore no anger towards them because what God wills is what happens.

Eyiche Adizua, now a retired technician, was scout and fisherman during the civil war.

Photo: Shayera Dark

Eyiche Adizua, Technician and Fisherman

I was a scout working to ensure Oguta didn’t fall in the hands of the Nigerian army as there were people crossing the lake into town. During the invasion, soldiers burnt houses and killed civilians, including old women and men. My elderly uncle was murdered. The lake was filled with dead bodies, including those of white mercenaries.

Prior, I worked for National Electric Power Authority (NEPA) in Lagos and was secretary to the Worker’s Union. But after Nigeria declared war on Biafra and some soldiers visited my house while I was away, thinking I was a Biafran informant, I quickly left Lagos.

During the war, refugees from Rivers came to Oguta. I housed two families and fished in the lake to make ends meet. Some people in Oguta died from Kwashiorkor because of the military blockade that barred relief materials from entering Biafra.

When Oguta was attacked, I went with my kids to neighbouring Egwe, where we stayed for two weeks. Some of the townspeople were hostile to Oguta people, assuming we’d purposely allowed the Nigerian army in. But some were kind to us.

After the war, life in Oguta was difficult because there was no money. However, there was a huge flood that brought plenty of fish, so there was a lot to eat. The charity Caritas International also provided relief materials. I got back my job at NEPA and was paid my salary that had accumulated during the thirty-month conflict. However, I asked to be posted to Oji River in Enugu because I heard it wasn’t safe for Easterners to return to Lagos.

I supported Biafra solely because the authorities promised to open Orashi River to the sea, which would have made Oguta a seaport and brought wealth to the town.

Personally, I won’t subscribe to war today because I saw war. One united Nigeria is better. That said, citizens should be allowed to run and win elections in any part of the country.

You May Also Like